I. Introduction

Israel had long been warned that disobedience would lead to captivity. Jerusalem fell, many were exiled, and empires changed hands. Daniel not only foretold the rise of Persia—he also lived through the transfer of power as God’s people remained in exile. Esther takes place in the Persian Empire after Babylon fell, when many Jews still lived scattered across the provinces rather than returning to Jerusalem.

And here’s the tension Esther forces us to face: what does God’s faithfulness look like when you can’t “see” it—when you’re far from Jerusalem, under pagan rule, and God’s name is never even mentioned?

Esther answers that question with a story of reversals: a queen removed, an orphan elevated, a murderous decree issued, and an enemy destroyed by the very outcome he intended for God’s people. God is not named in the book, but His providence is written all over it. Providence is God quietly governing events—without visible miracles—so His promises still stand.

Today we’ll watch how God preserves His people through ordinary decisions, flawed rulers, and perfectly-timed reversals. The reversals aren’t accidental—they’re the means God uses to preserve His covenant people.

II. Background History

We’re going to need more than a single lunch hour together to fully recap the book of Esther. The history, the life lessons, the imagery, the symbolism in Esther is amazing. I encourage you to read this story in its entirety to see God’s faithfulness.

We have a movie today to review, full of twists and turns, love and betrayal, good versus evil. There’s a large cast of characters with many conflicting motives, so I hope you brought popcorn for lunch.

But first, let’s talk about the book itself. The book of Esther is a historical novella, intended to teach the Jewish people of the history and significance of the feast of Purim. The book is interesting for what it does not mention. It doesn’t mention God, or the Law, or the Torah, or Jerusalem. It’s a story. A story of a simple Jewish girl and her uncle and how they live by faith in a hostile land.

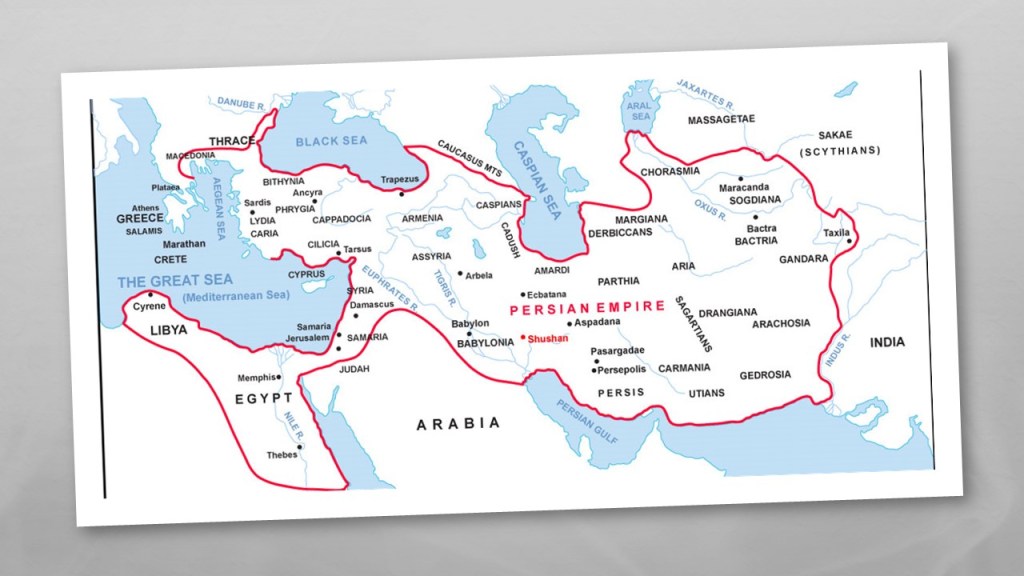

Both lived in the ancient kingdom of Persia under the king Ahasuerus, probably from 486-465 BC. Persia at this time was huge; the book of Esther, chapter 1:1, says it included 127 provinces. Modern countries which were once part of the Persian Empire include northern Greece, Macedonia, Bulgaria, Turkey, Syria, Lebanon, Israel and Palestine, Jordan, Turkey, Armenia, Georgia, Abkhazia, Chechnya, Ossetia regions, Azerbaijan, Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Egypt, parts of Libya and Sudan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, parts of Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, Afghanistan, Pakistan and parts of Kyrgyzstan.

That’s a huge swath of civilization. And somehow a simple Jewish girl in exile becomes the Queen of Persia and saves her people from genocide.

Well, you can’t have a soap opera without a cast of characters. The good, the bad, and the ugly.

The good:

Mordecai the Jew. He’s the son of Jair, tribe of Benjamin. He lives in Susa in the center of Persia. The Talmud records his name as Mordechai Bilshan, and he’s also mentioned in Ezra 2:2 and Nehemiah 7:7 as one of the exiles who returned to Jerusalem to rebuild the temple under the Persian king Cyrus. We know that was in approximately 537 BC, which means Mordecai is about 64 years old. Interestingly, the Talmud also lists Mordecai as a prophet who prophesied in the second year of King Darius, and also lists Mordecai as a direct descendant of Kish who is the father of the 1st king of Israel, Saul.

In Esther 2:7,

“And he brought up Hadassah, that is, Esther, his uncle’s daughter: for she had neither father nor mother, and the maid was fair and beautiful; whom Mordecai, when her father and mother were dead, took for his own daughter.”

So, Esther is actually Mordecai’s cousin, though Mordecai is the much older of the two, and since he adopted Esther as his own daughter, he’s also her uncle.

We also have Esther who is called Hadassah. She’s a Jewish orphan girl. Esther is her Persian name, Hadassah is her Hebrew name. Mordecai forbids Esther to reveal her nationality and family background, so when she’s around Persians, she’s Esther. She’s described as beautiful and having a lovely figure.

The bad (well… not “all the same kind” of bad—some of this is flawed rulers and palace politics, and some of it is genuinely evil):

The king of Persia is Ahasuerus, which is a weird name. Ahasuerus is a Latin word which is derived from a Hebrew word. Other translations begin with a Greek word and is translated Xerxes. Both are right, but since Ahasuerus is so hard to spell and pronounce, I’m going to call him Xerxes.

Queen Vashti. Traditional Jewish teachings about Vashti describe her as wicked and vain, the great-granddaughter of Nebuchadnezzar II of Babylon. She’s married to Xerxes. At least, for now.

And we’ll meet the worst of the bunch in Scene 3—Haman.

The ugly:

Attendant-guy. He doesn’t actually have a name, unless it’s Harbona from Esther 7:9. But we need him to be an extra in our movie, but he doesn’t get his name listed when the credits roll at the end.

III. Scene 1, Esther 1. The Old Queen is Vanquished.

As our story of Esther opens in Esther 1:1, Ahasuerus, I mean Xerxes, is holding a massive celebration. And I mean massive. It is a celebration that lasts 6 months long. I think the sole purpose of the celebration was to demonstrate that Xerxes had a lot of money and could party for 6 months. And at the end of the 6 months of partying, Xerxes isn’t done. Xerxes then throws a second banquet in an enclosed garden of his palace for his closest friends and advisors, this one lasting an additional seven days. There are wall hangings of the finest linen, couches made of gold and silver, on floors made with marble and mother-of-pearl. And it says in verse 8,

“By the king’s command each guest was allowed to drink with no restrictions, for the king instructed all the wine stewards to serve each man what he wished.”

So at the end of this week long binge, Xerxes is completely drunk. He nudges his friends, “Man, my wife is hot. You guys want to see her? Hey, attendant-guy, whatever your name is, fetch my wife Vashti. Tell her to wear her crown.”

Vashti is in the palace. She’s been holding her own banquet next door at the same time. The attendant-guy shows up and says to Vashti, “The Great and Powerful Xerxes summons you to the enclosed garden of drunk men. PS. Wear your crown.” Vashti says, “I don’t think so.”

So attendant-guy goes back to Xerxes and says, “Vashti says no.” And the king is mad. He’s furious that Queen Vashti won’t come to parade before his drunk buddies wearing her crown. He asks his drunk friends what they think he should do, and they say, She can’t tell you ‘no,’ you’re the king. If this gets out, no wife will ever appear before their husband. On demand. Wearing a crown.”

I’m thinking that week-long drinking binge isn’t the best environment for making serious decisions. It’s clear from the context that Xerxes wasn’t trying to complement his wife, but to show her off as a trophy to his drunken friends. After she refuses, King Xerxes doesn’t lash out at her but instead looks for a way to manipulate the law of the land to punish her and redeem his pride.

Pretending he’s helping all husbands in the kingdom, Xerxes banished Vashti from ever seeing Xerxes again, and her position as Queen will be given to somebody else.

And here’s where the theme of the whole book starts to show up: what looks like a drunken, impulsive decision becomes the first domino in a chain of events that will end up preserving God’s people.

Exit Vashti, stage left. End Scene 1.

IV. Scene 2, Esther 2. The New Queen is Appointed.

As we move into chapter 2, Xerxes is recovering from his hangover. One of his advisors suggests that Xerxes should hold the world’s first Ms. Persia contest and then Xerxes can select whoever he wants. Now, let’s be clear—this isn’t really a “contest” the way we think of it today. This is the machinery of a royal harem. Beautiful young women throughout the kingdom are gathered into the palace, and the king will choose.

All of the beautiful young virgins throughout the kingdom are to be brought to the palace and given spa treatments until they’re ready to see the king. Esther 2 is surprisingly specific about what that looked like: a full year of preparation—twelve months—before any woman was brought to the king.

Enter Mordecai and Esther. Esther is taken to the palace and placed in the care of the king’s eunuch, Hegai, who takes special care of her. She’s provided with beauty treatments and special food and seven attendants to take care of her, while Mordecai checks on her daily. He cautions her not to reveal that she’s a Jewish orphan.

After a full year of beauty treatments, she’s taken to King Xerxes, who likes what he sees. Xerxes says, “Hey, attendant-guy, whatever your name is. Get this girl a crown.”

Esther is made Queen of Persia. A simple Jewish orphan, now in the palace with a crown on her head. An incredible turn of events for her.

You know, we’ve been talking about how God equips us today for today, and the story of this faithful Jewish orphan girl demonstrates God’s providence. Through a series of “coincidences,” Esther is elevated to a very high status—the Queen of Persia. How did she arrive here? Humanly speaking, by being swept into a pagan system she did not design, by listening to Mordecai’s counsel, and yes, by the beauty God gave her. But the deeper point isn’t that beauty is the “key” to God’s plan—it’s that God can position His people inside circumstances they never would have chosen, and still use them for His purposes.

And Mordecai? He’s exactly where God wants him, too. During his daily visits to check on Esther, he overhears a plot to assassinate the king. He passes the news to Esther who in turn reports it to the king. Mordecai’s actions are investigated and recorded in the king’s diary. And here is an important detail that matters later: the deed is written down, but Mordecai is not rewarded—not then. It’s filed away as a footnote in the palace records.

We’re supposed to be faithful where God has placed us, even when the government is pagan and the culture is hostile. Mordecai does the right thing, and he protects the king’s life. But by doing the right thing, Mordecai gains some unwanted attention. Up to now he’s been happy as just a simple Jew living in exile.

And one more domino falls into place: Esther is in the palace, Mordecai’s loyalty is on the record, and nobody realizes yet how those two threads are going to come together.

Discussion Question (Scene 2): Where have you seen God put someone in the right place at the right time?

V. Scene 3, Esther 3. The Dark Side.

In Chapter 3 of Esther, the plot thickens, mwahaha. Enter the villain of our lesson, Haman. In Esther 3:1-2,

After these events, King Xerxes honored Haman son of Hammedatha, the Agagite, elevating him and giving him a seat of honor higher than that of all the other nobles.

And it’s worth noting: that phrase “after these events” may cover a significant span of time. Esther has been queen for a while when Haman rises to power. This isn’t necessarily the next day. But the camera cuts from Mordecai saving the king in Chapter 2 to Haman being elevated in Chapter 3—and you can feel something ominous coming.

I’ve always wondered about this. Chapter 2 ends with Mordecai foiling the assassination, and Chapter 3 begins with “After these events,” and Haman is honored. Is it because Mordecai was a Jew? Was it because Haman took credit?

This is ominous. Haman is called an Agagite—connected to Agag, king of the Amalekites—Israel’s ancient enemy. The Amalekites were a tribe from Canaan who have constantly been harassing the Israelites throughout history, from the Exodus out of Egypt throughout the reign of David. In Exodus 17:8-16, around 1440 B.C, just after Moses struck the rock and the water flowed, the Amalekites attacked the Israelites. Joshua led the battle against the Amalekites, and Moses stood on top of a hill with his arms raised in glory to the Lord while Aaron and Hur held his arms up. When the Amalekite army fled, Exodus 17:14-16 says,

Then the LORD said to Moses, “Write this on a scroll as something to be remembered and make sure that Joshua hears it, because I will completely blot out the memory of Amalek from under heaven.” Moses built an altar and called it The LORD is my Banner. He said, “For hands were lifted up to the throne of the LORD. The LORD will be at war against the Amalekites from generation to generation.”

These are the Amalekites from whom Haman is descended. Then, 400 years later around 1040 B.C, the book of 1 Samuel chapter 15, Saul is commanded by the Lord. This is the same Saul from whom Mordecai is related. 1 Samuel 15:1-3, it says,

Samuel said to Saul, “I am the one the LORD sent to anoint you king over his people Israel; so listen now to the message from the LORD. This is what the LORD Almighty says: ‘I will punish the Amalekites for what they did to Israel when they waylaid them as they came up from Egypt. Now go, attack the Amalekites and totally destroy everything that belongs to them. Do not spare them; put to death men and women, children and infants, cattle and sheep, camels and donkeys.’ “

God commanded Saul to put all of the Amalekites to death, but Saul gets this idea to spare King Agag of the Amalekites and keep the sheep and cattle and fat calves and lambs. The Lord was trying to protect Israel by ordering Israel to destroy the Amalekites, and the Amalekites kept coming back and attacking Israel.

Now, another 500 years pass, and now we find Haman, an Amalekite and descendent of Agag, has been elevated to a position of power in the kingdom of Persia where the Israelites live. This is really bad news for the Jews like Mordecai and Esther living there.

King Xerxes orders all the royal officials to bow down and pay honor to Haman. Mordecai refuses to bow down. Now, it’s not against Jewish law to bow down and give respect. The Jews bowed down before their own kings in other books of the bible, like 1st and 2nd Samuel and in 1st Kings. And Mordecai also almost certainly bowed down to King Xerxes or he wouldn’t be alive.

Some scholars believe that one reason Mordecai would not bow may be that as a descendent of Agag, Haman would believe he was divine or semi-divine, a god. Mordecai would certainly not bow down before another god. Other scholars believe it was simply because Mordecai would not bow down before an enemy of God, an Amalekite who hated Jews. Either way, Mordecai draws a line he won’t cross—and Haman makes it personal.

Haman was enraged that this one man would not pay homage to him, and when Haman found out Mordecai was a Jew, he wasn’t satisfied with just killing Mordecai. No, Haman decided this would be his chance to destroy all the Jews. A religious, ethnic cleansing.

Verse 8-9,

Then Haman said to King Xerxes, “There is a certain people dispersed and scattered among the peoples in all the provinces of your kingdom whose customs are different from those of all other people and who do not obey the king’s laws; it is not in the king’s best interest to tolerate them. If it pleases the king, let a decree be issued to destroy them, and I will put ten thousand talents of silver into the royal treasury for the men who carry out this business.”

Ten thousand talents of silver—an absurd sum, basically a fortune offered to fund genocide.

Haman could not come right out and tell King Xerxes he wanted to kill all the Jews. Xerxes would know that the Jews were loyal subjects; Mordecai had himself saved King Xerxes life. So Haman mixes in half-truths… a “certain” people. They’re… “different.” They don’t… “obey.” You shouldn’t have to “tolerate” them. He never names the Jews—he just paints them as a problem that needs to be “handled.” By laying out an incomplete picture with half-truths, Haman was able to convince the King that these “certain people” should be killed, and the King signs the death warrant.

And here’s the mechanism that makes this so dangerous: the king hands Haman the signet ring. With that ring, Haman can seal the decree with the authority of the throne. In Persia, once that law goes out, it doesn’t just get “undone” with a quick apology.

Persia was a big empire, and this ethnic cleansing could not happen immediately. Haman decided the annihilation would occur in the twelfth month of Adar, about a year away. And Haman doesn’t just pick a date—he casts lots, “pur,” which is where “Purim” will get its name. All the royal secretaries were summoned, and the decree was written in every language of Persia and then distributed to all the governors in all the provinces. The Jews have a year to live.

And the scene ends with one of the darkest, most cinematic images in the whole book: the couriers race out with the decree, the city of Susa is left confused and bewildered… and the king and Haman sit down for a drink.

End Scene 3.

VI. Scene 4, Esther 4. If I Perish, I Perish.

Mordecai is troubled. He now realizes Haman has used Mordecai’s refusal as the excuse to target all the Jews. Esther 4:1 –

When Mordecai learned of all that had been done, he tore his clothes, put on sackcloth and ashes, and went out into the city, wailing loudly and bitterly.

Part of this was a public display against the orders of the king, but most of it was probably genuine grief. He’s going to die. All of his loved ones are going to die. All of the people of his faith are going to die. Verse 2,

But he went only as far as the king’s gate, because no one clothed in sackcloth was allowed to enter it.

Apparently they had some sort of dress code and Mordecai was not allowed inside wearing sackcloth and ashes. Verse 3,

In every province to which the edict and order of the king came, there was great mourning among the Jews, with fasting, weeping and wailing. Many lay in sackcloth and ashes.

And notice this: in the Bible, fasting is rarely just “going hungry.” Fasting is what people do when they have no leverage left—when they are seeking God’s help and God’s mercy, even when God’s name isn’t being spoken out loud in the story.

All of the Jewish people are scared, mourning, praying, crying. Mordecai sends a message to Esther, who’s protected inside the palace. Mordecai tells Esther to go to the king and beg for mercy for the Jews.

This is a terrifying request to Esther. As queen, Esther did not have a husband/wife relationship like we understand it today. Esther was a servant of the king, and she could only appear to him when summoned. In Persia, you don’t “drop by” the king—unsummoned access could mean death unless he extends the scepter. The law was strict – if you crash the king’s party, you die. There was a possibility that the king could hold out his golden scepter and your life would be spared. But whatever relationship Esther and the king had, it was not currently in the best of conditions. Esther had not been summoned by the king for 30 days. She was certain that to appear before the king would mean her death.

How do we understand God, who created us and everything we see? Do we decide who He is, and then assume God will do our will? Or do we decide to be obedient and try to understand what God wants? Do we stay safe, keep silent, avoid taking risks? Or do we try to be obedient?

Fear not. God’s got this. God will keep His promises—Esther’s question is whether she will be the instrument, and what it will cost her if she refuses. We can choose to participate, be a spectator, or deny Him altogether, but we cannot thwart God’s will. God sees history all at once, past, present and future. God creates us for a purpose and plants us right where we are. Your job, your family, your pretty face, your intelligent brain, your feelings, your money, your talents have all come together for this one instant, this one instant that will never occur again. In another minute, in another hour, this moment will have passed.

Mordecai knows all this. Esther is exactly where God put her. God removed Vashti and placed Esther as queen. She had every resource she needed to do God’s will. But will she do it? Will she risk everything given to her to do what God wants her to do? God had given Esther so much. God gave her external beauty, and it was her beauty that gave her and her alone access to the king. Would she put her beauty on the line and risk death? God gave her position – she was queen and had access like nobody else. Would she put her position as queen on the line and risk death? Esther also had her inner beauty and love for her people. Most important, Esther had the entire kingdom of heaven behind her. She had everything she needed, but would she risk it, or would fear hold her back?

Mordecai delivers at this point one of the most memorable lines of the bible. He tells Esther that deliverance will come—God will accomplish His purpose. Silence isn’t neutral here. If Esther will not do it, then God will save His chosen people another way. Esther’s choice is whether she is going to participate in God’s plan and realize that her entire being, her beauty and position, was orchestrated by God, and God will accomplish His will through His obedient people. Mordecai also tells her that if she’s trying to save her own skin, she’s probably going to lose that, too. She’s a Jew – if the Jews are eliminated, that includes her. She cannot save her own life. All she can do is choose to be obedient, or not. Mordecai says in verse 13-14,

“Do not think that because you are in the king’s house you alone of all the Jews will escape. For if you remain silent at this time, relief and deliverance for the Jews will arise from another place, but you and your father’s family will perish. And who knows but that you have come to royal position for such a time as this?”

The entire purpose of Esther’s life had come to a point of decision. Her entire existence had a purpose. What was more important, being queen, or being the liberator of the Jews? God will not fail to keep His promises or fall short of His purposes, therefore, the deliverance of the Jews was certain. God had made Esther queen so that she could deliver His people. God places people exactly where they can serve Him.

And here’s how to be faithful, Esther’s response to Mordecai is equally as famous as his question in verses 15-16–

Then Esther sent this reply to Mordecai: “Go, gather together all the Jews who are in Susa, and fast for me. Do not eat or drink for three days, night or day. I and my attendants will fast as you do. When this is done, I will go to the king, even though it is against the law. And if I perish, I perish.”

“If I perish, I perish.” That’s not recklessness—that’s surrender. Jesus later teaches the same kind of logic: don’t cling to this life as your treasure. Don’t fear the one who can kill the body but cannot kill the soul. As Christians, we are free of death so that we may live, and Esther’s response to the fear of losing her life is perfect. If I perish, I perish.

End Scene 4.

Discussion Question (Scene 4): Where do you feel the pull between staying safe and doing what’s right, and what would “for such a time as this” look like there?

VII. Scene 5, Esther 5. Rise of the Queen

Despite the decrees of the land and the fear of death, Esther dresses in her finest royal robes and enters the inner court of the palace in front of the king’s hall. And much to Esther’s surprise, the king is glad to see her. King Xerxes holds out his golden scepter, and Queen Esther approaches—and she comes close enough to touch the tip of the scepter.

And the king says, “Are you wearing a crown? That is so cool.”

No seriously, he is so pleased to see her, the King tells Esther to ask for anything, and the king will give it to her—“up to half the kingdom.” That’s royal promise-language. It doesn’t mean he’s going to hand her Persia on a deed and a title, but it does mean: I’m listening. Name your request.

Queen Esther bats her long lashes at Xerxes – actually, that part isn’t in scripture, but it’s easy to imagine it being true. She bats her eyes at Xerxes and says, “Would you like to come over to dinner tonight? I’d like to ask my favor of you over a nice candlelight dinner. Just you and me…. And Haman?”

And the king I’m sure is like, what? Haman, too? Sure. Why not. Let’s have dinner tonight. Somebody fetch Haman.

So this is Banquet #1. Esther has a plan, but she’s not going to play her hand all at once.

Haman should be having a good day. Scripture says in the latter half of Esther 5 that as soon as Haman sees Mordecai at the King’s gate, still sitting there because of that dress code, Mordecai doesn’t rise for Haman, doesn’t bow to Haman, isn’t afraid of Haman. Mordecai does not rise or tremble. And Haman is filled with rage. And he is still filled with rage when he gets home.

Haman’s family and friends are there and Haman gets the invitation to the queen’s banquet. And Haman starts bragging. Look at all my wealth. Look at all my power. And I am the only person invited to have dinner with the King and Queen. But while Mordecai defies me, I will never be happy.

Haman’s wife, Zeresh, says, just ask the king to hang him. You’re buddies, he’ll do that for you, right? And Haman smiles a wicked smile.

Haman erects a huge gallows outside his house—basically a massive pole. Esther 5:14 says it’s fifty cubits tall, which works out to about 75 feet. That’s like twice the size of a Texas pine tree and even bigger than the egos of most politicians! I mean, it’s huuuge. And when the king tells Haman it’s ok to hang Mordecai, he’s going to hang Mordecai high on this thing outside of his own house.

And with the gallows built, Haman plans to go to the king in the morning and get permission to do it.

End Scene 5.

VIII. Scene 6, Esther 6. A Sleepless Night.

Scene 6 opens with the King unable to sleep. And this is one of those “small cause, huge effect” moments. One sleepless night is about to flip the entire story.

I like to think the King is excited about his upcoming dinner date with his queen, Esther. And Haman. Apparently attendant-guy or somebody like him writes down everything that happens in the king’s life. Kind of like keeping a diary, but somebody else fills in the pages for you. In the text it’s the royal chronicles—the official record of the kingdom.

And the scene gets even better: the record isn’t just brought in, it’s read to the king. So the king is listening to his own chronicles like it’s some sort of murder mystery novel.

Do you remember all the way back to Scene 2 where Mordecai overheard about the plot to assassinate the king? The king hears the story again and says, did we give this guy a gold medal or something for saving my life? And attendant-guy says, nope. We didn’t do diddly squat for him. Diddly squat is the ancient Hebrew.

So the king says, I need some ideas on how to honor this guy Mordecai. Who’s hanging around in the lobby?

And here’s the timing that makes this scene perfect: it’s early morning, and Haman is already in the outer court. Why? Because he’s there to ask permission to hang Mordecai on that huge gallows he built the night before.

Haman, bring him in.

Hey Haman, if I wanted to give somebody some special recognition, what do you think I should do?

And Haman thinks, “Wow, the king is thinking about me.” And Haman says, “A parade! A parade with horses and a special robe and trumpets and stuff!”

The text gets very specific. Haman says: give the man a royal robe—the kind the king himself has worn. Put him on a horse the king has ridden. Put a royal crown or crest on the horse’s head. And then have one of the king’s highest officials lead him through the city streets proclaiming, “This is what is done for the man the king delights to honor!”

And the king says, “Great idea! Haman, go get a fancy robe and throw a parade for Mordecai!”

And the reversal is complete: Haman doesn’t just have to watch Mordecai be honored—Haman has to lead him. Haman has to put the robe on Mordecai. Haman has to walk him through the city. Haman has to announce his honor out loud.

And Haman does what the king says, but you know it just rotted his socks to put a fancy robe on Mordecai and parade him around the city.

After the parade, Haman rushes home, mourning, covering his head, humiliated. And he doesn’t get to mourn long, because the king’s eunuchs arrive and rush him out the door to take him to that fancy schmancy dinner with the King and Esther.

No miracles. No prophets. Just timing that’s too perfect to dismiss.

End Scene 6.

IX. Scene 7, Esther 7. The Dark Side Destroyed.

Scene 7, the banquet. The king is there. The queen is there, batting her eyes. Haman is there, grumpy from the parade he had to throw for Mordecai.

The king and queen gaze longingly into each other’s eyes. And the king says, have you thought about what sort of present you would like? In the text it’s more formal: “What is your petition? What is your request? It will be granted.”

And Esther finally plays her hand. She doesn’t begin with politics. She begins with life and death.

Esther says, “If I have found favor in your sight, O king… spare my life.” And then she adds, “and spare my people.”

And here’s the twist: the decree she’s talking about isn’t some rogue order from a distant governor. It’s the king’s own decree—sealed with his own authority. Xerxes is suddenly hearing, for the first time, what his signature actually authorized.

Then verses 5 & 6 — I think the King had no idea that there was a decree that would kill all the Jews,

King Xerxes asked Queen Esther, “Who is he? Where is he—the man who has dared to do such a thing?”

Esther said, “An adversary and enemy! This vile Haman!”

The room goes cold. Haman’s face drops. And the king explodes with rage.

The king gets up from the banquet in anger and storms out into the palace garden. Xerxes is outside, pacing, furious… realizing he has been manipulated, and realizing the decree is his.

Meanwhile, Haman is inside, and now he’s terrified. He begs Queen Esther for his life. And in his panic, he throws himself on the couch where Esther is reclining.

And at that exact moment, Xerxes comes back in from the garden and sees it. He sees Haman on Esther’s couch, looming over her, pleading, flailing—whatever it looked like, it looked bad. And Xerxes barks out the line that seals Haman’s fate: “Will he even assault the queen in my presence?”

That’s it. The guards cover Haman’s face. It’s over.

And now—enter attendant-guy. The moment he’s been waiting for. Esther 7:9 finally gives us the name. Harbona.

Harbona speaks up and says, you know, there’s this huge gallows—this giant pole—just outside of Haman’s house. The one Haman built for Mordecai. The one that’s taller than two Texas pine trees.

Verse 9b-10,

The king said, “Impale him on it!” So they impaled Haman on the pole he had set up for Mordecai. Then the king’s fury subsided.

And that’s the reversal Esther has been building toward all along: the enemy is destroyed by the very outcome he intended for God’s people. No miracles. No prophets. Just providence—God turning evil back on itself.

End Scene 7.

X. Scene 8, Esther 8-10. They All Lived Happily Ever After. The End.

Scene 8, they all lived happily ever after. The king gave Esther everything that Haman owned, Mordecai was given a place in the palace, and the authority of the empire shifted. Remember that signet ring? The ring that made Haman’s decree unstoppable? Xerxes takes it off Haman’s hand and gives it to Mordecai. The symbol of power changes hands, and the story’s reversal is now official.

But here’s an important detail: Haman’s order to destroy the Jews was not simply “revoked” like an email that gets recalled. Persian law doesn’t work that way. The first decree still exists. So the solution is a second decree—a counter-decree—written with the king’s authority and sealed with that same signet ring. The new decree authorizes the Jews throughout the provinces to assemble and defend themselves on the appointed day.

And that matters, because the danger wasn’t imaginary. The Jews still had to stand together, prepare, and defend themselves against those who would attack them. Deliverance came through a reversal of power and permission: what was meant for their destruction became the very occasion where God preserved them, and their enemies fell into the trap they helped set.

The feast of Purim was established to memorialize the Jews rescued from certain death and destruction. And even the name is a final irony: Haman cast lots—pur—to pick the day of annihilation, and that “pur” becomes Purim, the annual reminder that God can overturn what looks certain.

Even though God was not mentioned in the book of Esther, God’s hand was evident in the saving of His people. Even in captivity in a foreign land, God protected His people.

We, too, are protected, though we live in a foreign land. 1 Peter 2:11 calls Christians “foreigners and exiles” as we live in our pagan society. But God has not abandoned us here. His protection surrounds us, and God asks us to trust in Him for that protection.

Discussion Question (Scene 8): When God feels “hidden,” what helps you keep trusting Him?

And as the book of Esther ends and the credits roll across the screen, there’s one more image: Mordecai is elevated—great among the Jews, respected in the kingdom—using his position not for himself, but for the welfare of his people.

And there’s still a huge pole that’s been erected, taller than two Texas pine trees, that saves us and destroys the enemy. Christ hangs upon that tree, defeating death and taking on our sins so that one day we too, live in eternity, happily ever after.

The End.

Or should I say,

It is Finished.

To God be the glory.

Leave a comment