Introduction: Contextual Background

So we’re going to cover Matthew 18, several parables together, so it’s going to feel like we’re moving quickly. But there’s a theme, a purpose to Matthew’s writings, so it’s important to understand before the study how this chapter fits within the larger story of Jesus’ ministry. Matthew’s Gospel is organized in a rhythmic, back-and-forth movement between narrative history, then into discourse material, major themes and purposes provided by Jesus.

In understanding Matthew 18, it’s important to note the historical and cultural context in which Matthew wrote. His audience, primarily Jewish, was familiar with the teachings of the Torah and the prophets. This background influenced how they understood Jesus’ teachings about the kingdom of heaven. Let’s keep this in mind as it sheds light on the meanings behind Jesus’ words.

The Gospel contains five major discourses, akin to the five fingers on a hand, making them readily memorable. Each section corresponds to a vital question that Jesus addresses:

- How are citizens of the kingdom to live? This is covered in the Sermon on the Mount in chapters 5 through 7.

- How are traveling disciples to conduct themselves on their evangelistic journeys? This is found in chapter 10.

- What parables did Jesus tell to illustrate the truths of the Kingdom? These are recorded in chapter 13.

- What warnings did Jesus give about not hindering entrance into the kingdom and on forgiveness? This is what we find in chapters 18 through 20, which is our current focus.

- How will human history end? Jesus speaks on eschatology in chapters 24 and 25.

To signal the end of each discourse section, Matthew employs a distinctive formula: “when Jesus had finished [these sayings]” (Matt. 7:28; 11:1; 13:53; 19:1; 26:1). It’s like a marker, indicating the conclusion of one segment and the transition to another.

Today we’re beginning the fourth great discourse. By the time we reach the eighteenth chapter, Jesus has already embarked on His public ministry. He has been baptized by John, faced temptation in the wilderness, and has begun His work in Galilee. We’ve seen Him call His first disciples, deliver the Sermon on the Mount, and perform numerous miracles. Jesus has fed thousands with just a few loaves of bread and fish, walked on water, and healed the sick, which not only demonstrate His divine power but also His compassion and concern for the physical and spiritual well-being of the people.

Jesus has also revealed more explicitly to His disciples the fate that awaits Him in Jerusalem — His suffering, death, and resurrection. The disciples are struggling with this revelation and what it means for them and their expectations of the Kingdom. They are still grappling with concepts of greatness and status in this Kingdom, which is evident from their question that opens this chapter.

Jesus is increasingly focusing on teaching His disciples about the nature of His Kingdom and what it means to live as part of this community. He’s preparing them for the time when He will no longer be with them physically, and the principles He sets out in Matthew 18 are essential for maintaining the integrity, unity, and health of the community of believers.

Therefore, Matthew 18 is not just a random collection of teachings; it is part of Jesus’ strategic preparation of His followers for the life of the Church after His ascension. He addresses issues like humility, community relationships, dealing with sin, and the ever-important principle of forgiveness — themes that are just as relevant for our community today as they were back then. Let’s keep this context in mind as we read and discuss the passage together.

Part 1: The Heart of the Kingdom – Humility and Childlikeness

Let’s begin with Matthew 18:1-6,

At that time the disciples came to Jesus and said, “Who then is greatest in the kingdom of heaven?” And He called a child to Himself and set him among them, and said, “Truly I say to you, unless you change and become like children, you will not enter the kingdom of heaven. So whoever will humble himself like this child, he is the greatest in the kingdom of heaven. And whoever receives one such child in My name, receives Me; but whoever causes one of these little ones who believe in Me to sin, it is better for him that a heavy millstone be hung around his neck, and that he be drowned in the depths of the sea.

Discussion question: What phrases or concepts stand out?

Discussion question: Why did the disciples want to know “who is the greatest in the kingdom of heaven?

I did some research on the phrase “kingdom of heaven,” and it was interesting. First of all, remember that Matthew’s primary audience is the Jews – not the gentiles or the pagans, but the Jews. And looking up this phrase took me down a rabbit hole, which I love.

The ‘kingdom of heaven’ is a term unique to Matthew’s Gospel. Unlike the other Gospel writers who primarily use the term ‘kingdom of God,’ Matthew opts for ‘kingdom of heaven’ almost exclusively. This choice is not accidental but deeply rooted in the Jewish culture and language from which Matthew is writing.

The Jewish tradition holds reverence for the name of God, often avoiding its direct mention. This reverence can be seen in Matthew’s substitution of ‘heaven’ for ‘God.’ Matthew uses “heaven” so as to avoid the direct use of God’s name in keeping with Jewish tradition. Heaven, in this context, is not merely a location but a representation of God’s space, authority, and the sphere where His will is enacted perfectly. So when Matthew speaks of the ‘kingdom of heaven,’ we’re speaking of God’s reign as it is in heaven being manifested on earth.

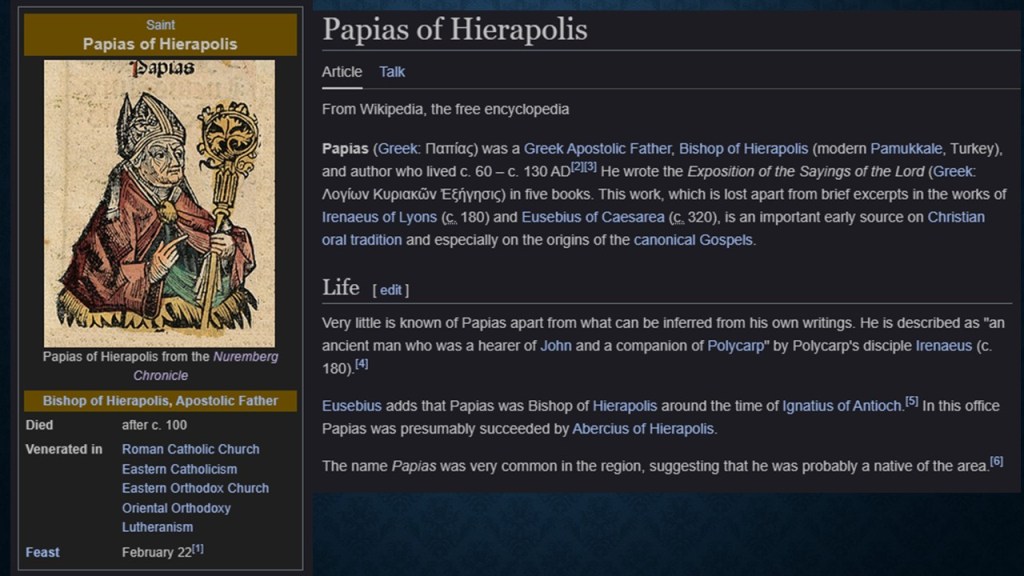

The Greek manuscripts of Matthew show that the Gospel was written in Greek. This was the language of the Eastern Roman Empire, which would have made the message accessible to a broader audience. However, the underlying Hebraic thought patterns and expressions suggest that Matthew was deeply familiar with Hebrew concepts and possibly oral traditions. Some early church figures, like Papias who lived from 60AD to 130AD, even suggest Matthew might have documented sayings of Jesus in Hebrew or Aramaic, though no such manuscripts have been found.

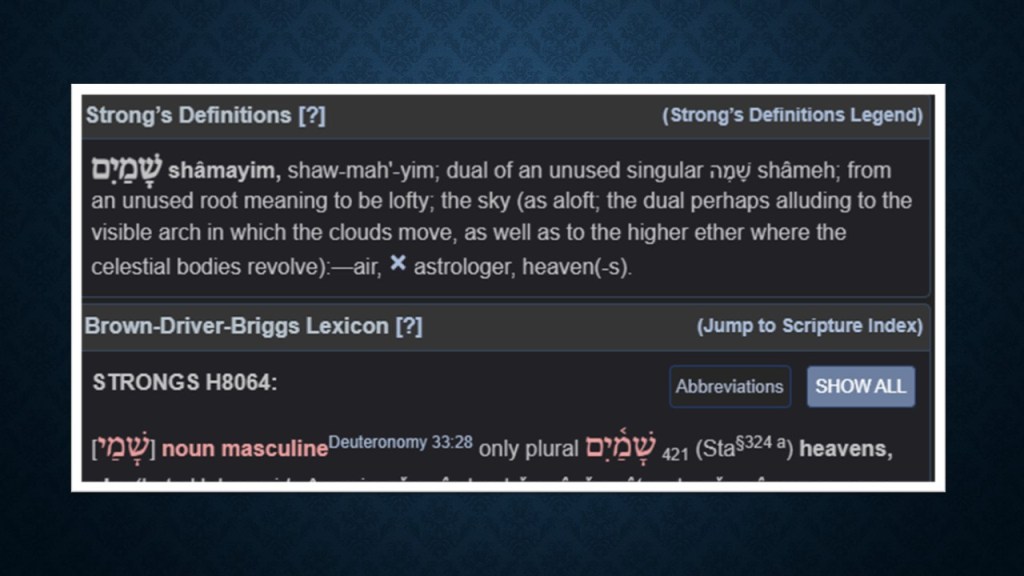

Matthew’s use of ‘heaven’ carries with it the duality of meaning present in the Hebrew word ‘Shamayim.’ It’s an interesting word that is neither singular or plural, but dual. Like the words “both” or “neither”. This word encompasses the physical skies above us, the dwelling place of God, and by extension, the reality of God’s rule. For Matthew’s Jewish audience, the ‘kingdom of heaven’ would resonate with the expectation of God’s rule both in the heavenly realm and on earth—a rule marked by justice, peace, and, as we’ll explore soon, humility.

Discussion question: What do you think Jesus mean by ‘become like children’?

Discussion question: What attributes of children do you think Jesus is encouraging us to emulate? Did He mean “immature?”

So, as we read about becoming like little children to enter this kingdom, we are reminded that it is not about childishness but about the childlike qualities of humility, trust, and openness that are essential to living under God’s reign. This teaching is not just about personal piety but about communal life—how we, as a church, embody the values of the kingdom of heaven here and now.

The disciples, at least at first, didn’t get it. Jesus said, “you will not enter the kingdom of heaven.” The force of these words to the disciples were staggering. Engaged in a debate over who would be the greatest in the kingdom, they were paradoxically demonstrating their lack of understanding of its true nature. The kingdom Jesus spoke of was fundamentally spiritual, its cornerstone being a humility of spirit. In their pursuit of self-glorification, the disciples were inadvertently distancing themselves from the very essence of the kingdom they sought to enter. Entrance into the kingdom was not about earthly status or hierarchy, but about embodying the humility and simplicity that Jesus taught.

Let’s keep in mind that Jesus is unveiling to us what life looks like when God’s will is done ‘on earth as it is in heaven.’ It’s a vision that challenges the worldly notions of power and greatness and calls us to a transformed community that reflects God’s love and righteousness.

Matthew 18 charges to become like little children, using the Greek term “ταπεινόω” (tapeinóō), which is often translated as ‘to humble oneself’. To fully appreciate this term, it’s essential to understand that ‘humility’ in the biblical sense diverges significantly from modern connotations of low self-esteem or self-deprecation. Biblical humility is not thinking poorly of oneself. I think such declarations of low opinions of oneself is actually some sort of perverted pride. Humility is not thinking of one’s self at all. It is a posture of the heart, an acknowledgement of one’s proper place before God and others. It implies a willing submission to God and a recognition of our dependence on Him, devoid of self-righteousness or arrogance.

The term ταπεινόω is active and intentional. It’s not something that happens to us; it’s a choice we make, a stance we adopt. It is about assessing ourselves correctly, without illusion or pretense, and positioning ourselves so that God can use us according to His will. This humility is what Jesus says is foundational to entering the kingdom of heaven, and it is characterized by the trust, openness, and dependency that we see in children.

Let’s cross-reference Psalm 131 from the Old Testament –

Lord, my heart is not proud, nor my eyes arrogant;

Nor do I involve myself in great matters,

Or in things too difficult for me.

I have certainly soothed and quieted my soul;

Like a weaned child resting against his mother,

My soul within me is like a weaned child.

Israel, wait for the Lord

From this time on and forever.

This Psalm is a beautiful depiction of humility. It doesn’t involve great acts of self-sacrifice or public declarations of piety. Instead, it is likened to a weaned child with its mother—a picture of contentment and rest. The weaned child is not grasping or needy, not clamoring for attention or demanding its way, but rather is settled and at peace in the presence of the one who provides care.

In Psalm 131, humility is also about quieting and calming oneself in the presence of the Lord, much like a child does in the arms of a caring parent. This Psalm reflects an inner state that is achieved through the relinquishment of personal ambition and the calming of the soul before God. It’s an invitation to find rest and peace in God’s care and provision, to trust Him fully.

Let’s consider another New Testament perspective on humility. James 4:10 tells us,

‘Humble yourselves before the Lord, and he will lift you up.’

This verse emphasizes a promise: God honors and elevates those who approach Him with a humble heart. It reminds us that our humility is not just about our posture towards others, but fundamentally about our posture before God. As we humble ourselves before the Lord, acknowledging our dependence on Him and setting aside self-importance, we open ourselves up to His guidance and upliftment.

Discussion question: How can we practice this kind of humility in our lives? How can humility transform our relationships with one another?

The dual picture presented by the Greek and Hebrew Scriptures reflect our prayer for the kingdom of earth to be as it is in heaven. It is a call to humble ourselves, to take our place as dependent children before God, trusting in His care, finding peace in His presence, and living out this trust and peace in our relationships within the community of believers. This is the humility that characterizes citizens of the kingdom of heaven. And as always, the perfect picture of this humility is Jesus Himself. Despite the fact that He was God Himself, Jesus demonstrated humility consistently.

Discussion question: How does this principle of childlike humility manifest in our daily interactions, decision-making, and in the way we approach our faith?

Part 2: Stumbling Blocks and Temptations

Let’s delve into Matthew 18:6-9,

“If anyone causes one of these little ones—those who believe in me—to stumble, it would be better for them to have a large millstone hung around their neck and to be drowned in the depths of the sea. Woe to the world because of the things that cause people to stumble! Such things must come, but woe to the person through whom they come! If your hand or your foot causes you to stumble, cut it off and throw it away. It is better for you to enter life maimed or crippled than to have two hands or two feet and be thrown into eternal fire. And if your eye causes you to stumble, gouge it out and throw it away. It is better for you to enter life with one eye than to have two eyes and be thrown into the fire of hell.”

Discussion question: What stands out to you in this passage?

Discussion question: Why do you think Jesus uses such strong imagery?

In this section, Jesus addresses a grave concern – causing others, especially those new or vulnerable in faith, to stumble or fall away from their path. The language Jesus uses here is intentionally vivid and alarming. The imagery of a millstone and the depths of the sea, the cutting off of limbs, and the gouging out of eyes – these are all hyperbolic but serve a purpose. They underscore the seriousness with which Jesus views the sin of leading others into temptation or sin.

This part of the discourse shifts the focus from our personal humility to our responsibility to our community of believers. It’s a stark warning against being a stumbling block to others. The term used here for “cause to stumble” is “σκανδαλίζω” (skandalizō), which is where we get the word ‘scandalize’. It originally referred to the trigger of a trap – an apt metaphor for leading someone into sin.

In the Jewish context, causing someone to stumble is not just a personal offense; it’s seen as disrupting the community’s harmony. It’s about leading someone away from the path of righteousness and truth, which in a communal faith like Judaism (and by extension, early Christianity), is a grave matter.

There are warnings in the Old Testament about leading others astray, such as in Leviticus 19:14,

“Do not curse the deaf or put a stumbling block in front of the blind, but fear your God. I am the LORD.”

This establishes the principle of not being a cause of harm or temptation to others, a principle Jesus is intensifying in this teaching.

Discussion question: What does this teach us about our responsibility towards others in our faith community?

Discussion question: How can we apply Jesus’ teaching about stumbling blocks in our own lives and communities?

Discussion question: In our modern context, what might be some ‘stumbling blocks’ we could unknowingly place before others, and how can we be more vigilant about these in our community?

In this passage, Jesus is not advocating self-mutilation but is emphasizing the need for radical action in avoiding sin and protecting others from sin. It’s about being acutely aware of the impact of our actions on others, especially on those who are vulnerable or new in their faith journey. This section challenges us to consider how our actions, words, and attitudes might be a hindrance to others and calls us to a higher standard of care and responsibility in our Christian walk.

Part 3: The Parable of the Lost Sheep

Let’s explore Matthew 18:10-14,

“See that you do not despise one of these little ones. For I tell you that their angels in heaven always see the face of my Father in heaven. What do you think? If a man owns a hundred sheep, and one of them wanders away, will he not leave the ninety-nine on the hillside and go to look for the one that wandered off? And if he finds it, truly I tell you, he is happier about that one sheep than about the ninety-nine that did not wander off. In the same way your Father in heaven is not willing that any of these little ones should perish.”

Discussion question: What does this parable tell us about God’s attitude towards the lost and the straying?

Discussion question: In what ways can we embody the shepherd’s actions in our own community?

This passage, known as the Parable of the Lost Sheep, shifts the focus to God’s care and concern for each individual, especially those who are lost or have strayed away. The imagery of a shepherd leaving ninety-nine sheep to find the one that is lost beautifully illustrates the value God places on each person. This parable is a powerful reminder of God’s relentless love and pursuit of those who are lost.

In the cultural context of Jesus’ time, a shepherd’s role was not just a job; it was a commitment to the welfare and safety of the flock. By leaving the ninety-nine, the shepherd demonstrates responsibility and care for each sheep.

I looked into the daily life of a shepherd in the days of Jesus, and here’s a list of responsibilities of the shepherd, a way of life that required a deep commitment and a constant vigilance.

Daily Activities of a Shepherd:

- Leading to Pasture: Each morning, shepherds led their flocks from the sheepfold, where they were kept safe during the night, to suitable grazing grounds. This often involved long walks to find green pastures, especially in the arid regions of the Middle East.

- Constant Vigilance and Protection: Throughout the day, the shepherd had to be alert to the dangers that the flock might face, such as predators (wolves, lions, or bears), thieves, or natural hazards. The shepherd’s tools – a rod for protection and a staff for guiding the sheep – were essential for this role.

- Providing Water: Shepherds also had to ensure that the sheep had access to water, which could mean leading them to streams or wells, or drawing water for them.

- Caring for the Vulnerable: Special attention was given to the young, the sick, or the injured sheep. This might involve carrying a lamb, applying oil to wounds, or ensuring the weaker sheep had access to good grazing spots.

- Bonding with the Flock: Shepherds spent a great deal of time with their flock, often developing a strong bond. The sheep would become familiar with the shepherd’s voice, a fact that Jesus alludes to in John 10:4, when He speaks of the sheep knowing the shepherd’s voice.

- Gathering the Flock: At the end of the day, the shepherd would gather the sheep, often counting them to ensure none were missing, and lead them back to the safety of the sheepfold.

The life of a shepherd was one of constant dedication and sacrifice. Their role was integral to the society and economy of the time, and their relationship with their flock served as a powerful metaphor for leadership and care in the biblical narrative.

Discussion question: How does the role of a shepherd, as depicted in this parable, translate into our roles as leaders, mentors, or members of our community today? How can we ‘seek the lost’ in our current environment?

In the Parable of the Lost Sheep, understanding the shepherd’s role in this context adds depth to Jesus’ message. The shepherd’s willingness to go after the lost sheep reflects not just a duty, but a deep care and commitment to the welfare of each individual within the flock. It is a vivid picture of God’s love and care for His people, emphasizing His willingness to go to great lengths to save the lost and bring them back into the fold. It’s a reminder that in God’s kingdom, each person is valued and worth the effort of rescue and restoration.

His Jewish listeners would understand all of this. Shepherding was a common but demanding occupation. The shepherd’s role as a caretaker and protector of the flock is a recurring theme in the Old Testament, symbolizing leadership and care. Jesus’ use of this imagery emphasizes God’s personal care and attention to each individual.

Let’s look at Ezekiel 34. It’s lengthy so I’m just going to do verses 2b, 3, 5, 6, and 11 –

God says: “Woe, shepherds of Israel who have been feeding themselves! Should the shepherds not feed the flock? You eat the fat and clothe yourselves with the wool, you slaughter the fat sheep without feeding the flock.

They scattered for lack of a shepherd, and they became food for every animal of the field and scattered. My flock strayed through all the mountains and on every high hill; My flock was scattered over all the surface of the earth, and there was no one to search or seek for them.”’

For the Lord God says this: “Behold, I Myself will search for My sheep and look after them.”

God himself is the shepherd of Israel. This chapter contrasts the failure of Israel’s leaders (shepherds) to care for their flock with God’s promise to personally shepherd His people.

Discussion question: Reflecting on this parable and God as our shepherd, how does this influence our view of and responsibility towards those who are lost or struggling in their faith?

Part 4: Restoring a Brother

Let’s read Matthew 18:15-20,

“If your brother or sister sins, go and point out their fault, just between the two of you. If they listen to you, you have won them over. But if they will not listen, take one or two others along, so that ‘every matter may be established by the testimony of two or three witnesses.’ If they still refuse to listen, tell it to the church; and if they refuse to listen even to the church, treat them as you would a pagan or a tax collector. Truly I tell you, whatever you bind on earth will be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth will be loosed in heaven. Again, truly I tell you that if two of you on earth agree about anything they ask for, it will be done for them by my Father in heaven. For where two or three gather in my name, there am I with them.”

Discussion question: What does this passage teach us about conflict resolution and reconciliation within the Christian community?

Discussion question: How does this process reflect the principles Jesus talked about in the Parable of the Lost Sheep?

In this passage, Jesus provides a practical framework for dealing with sin and conflict within the Christian community. It’s a step-by-step guide that emphasizes personal responsibility, communal accountability, and the ultimate goal of restoration and reconciliation.

The process starts with a private confrontation between the offended and the offender. This respects the dignity of the person who has sinned and provides an opportunity for private repentance and reconciliation. If this doesn’t resolve the issue, the next step involves bringing one or two others into the conversation to provide support, witness, and possibly mediation. The final step, if reconciliation is still not achieved, involves bringing the matter before the church community. This escalation is not about punishment, but about seeking restoration through communal effort.

The term “ἐκκλησία” (ekklēsia), often translated as ‘church’ or ‘assembly’, is used here by Jesus. In the context of Matthew’s Gospel, ἐκκλησία would likely have been understood as the local community of believers, not necessarily a formal church structure as we know it today.

This process can be compared to the Old Testament principle of establishing truth or judgment on the testimony of two or three witnesses, as seen in Deuteronomy 19:15 –

A single witness shall not rise up against a person regarding any wrongdoing or any sin that he commits; on the testimony of two or three witnesses a matter shall be confirmed.

This ensures fairness and prevents false accusations.

Discussion question: How can we apply this principle of lovingly and justly addressing sin within our community today? How do we do this in love instead of judgement?

Discussion question: This approach to conflict resolution, while challenging, is vital for the health and unity of our community. How can we cultivate a culture that values and effectively practices this biblical model of reconciliation?

Jesus’ teaching here underscores the balance between truth and love, justice and grace. It’s not just about correcting wrongdoing but about doing so in a way that maintains relationships and seeks the best for all involved. This passage challenges us to consider how we address conflict and sin within our own communities, encouraging us to act with a spirit of love, humility, and a desire for reconciliation, just as Christ does with us.

Part 5: The Parable of the Unforgiving Servant

Let’s explore Matthew 18:21-35,

Then Peter came to Jesus and asked, “Lord, how many times shall I forgive my brother or sister who sins against me? Up to seven times?” Jesus answered, “I tell you, not seven times, but seventy-seven times. Therefore, the kingdom of heaven is like a king who wanted to settle accounts with his servants. As he began the settlement, a man who owed him ten thousand bags of gold was brought to him. Since he was not able to pay, the master ordered that he and his wife and his children and all that he had be sold to repay the debt. At this, the servant fell on his knees before him. ‘Be patient with me,’ he begged, ‘and I will pay back everything.’ The servant’s master took pity on him, canceled the debt and let him go. But when that servant went out, he found one of his fellow servants who owed him a hundred silver coins. He grabbed him and began to choke him. ‘Pay back what you owe me!’ he demanded. His fellow servant fell to his knees and begged him, ‘Be patient with me, and I will pay it back.’ But he refused. Instead, he went off and had the man thrown into prison until he could pay the debt. When the other servants saw what had happened, they were outraged and went and told their master everything that had happened. Then the master called the servant in. ‘You wicked servant,’ he said, ‘I canceled all that debt of yours because you begged me to. Shouldn’t you have had mercy on your fellow servant just as I had on you?’ In anger his master handed him over to the jailers to be tortured, until he should pay back all he owed. This is how my heavenly Father will treat each of you unless you forgive your brother or sister from your heart.”

Discussion question: What is the central message of this parable about forgiveness?

Discussion question: How does this parable challenge our understanding and practice of forgiveness?

In this passage, Jesus tells the Parable of the Unforgiving Servant in response to Peter’s question about the limits of forgiveness. The parable illustrates the necessity of forgiveness in the Christian life, using the contrast between the immense debt forgiven by the king and the small debt held by the unforgiving servant.

The key lesson here is the boundless nature of God’s forgiveness towards us, and the expectation that we, in turn, should extend the same grace to others. The ten thousand bags of gold represent a debt impossible to repay, symbolizing the enormity of our own spiritual debt to God, which He forgives out of mercy. The refusal of the servant to forgive a comparatively minor debt underscores the hypocrisy and ingratitude that can afflict believers.

When Jesus says to forgive not seven times but seventy-seven times (or seventy times seven, as in some translations), He is using hyperbole to make the point that there should be no limit to our forgiveness. This teaching challenges the traditional understanding of forgiveness that was prevalent in Jewish culture at the time, which advocated a more limited approach.

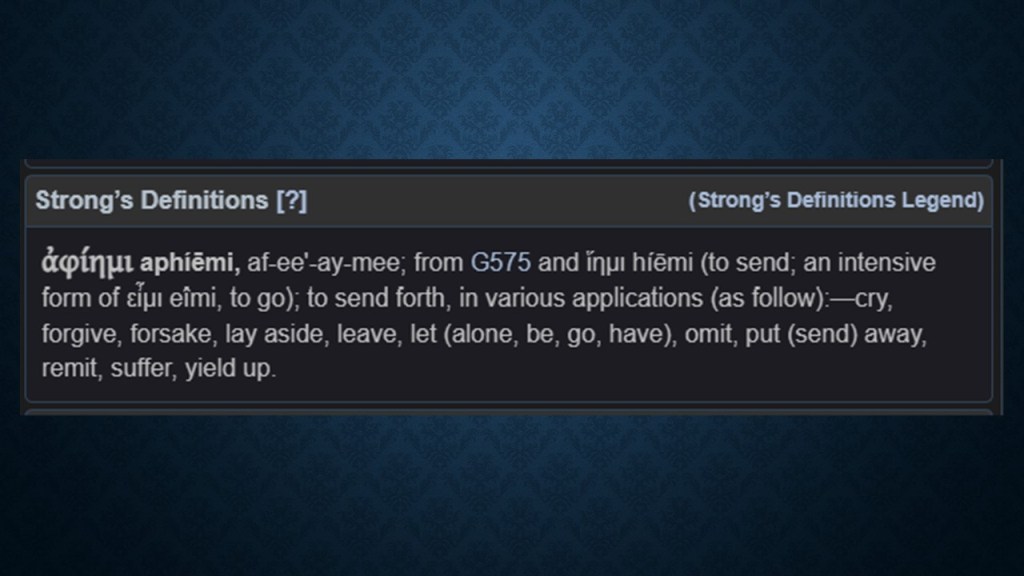

In the Parable of the Unforgiving Servant, a crucial word that Jesus uses is “ἀφίημι” (aphiēmi), typically translated as ‘forgive’ or ‘let go’. To fully appreciate the depth of this term in its biblical context, it is essential to understand its broader connotations in the original Greek language.

The term aphiēmi goes beyond the simple notion of pardoning an offense; it encompasses the act of releasing someone from an obligation or debt. In the cultural and historical context of the New Testament, debts were often seen as burdens or chains that tied the debtor to the creditor. Therefore, to forgive – in this sense – was to liberate someone from the weight of their debt, offering them a new start.

This understanding of forgiveness as a release is pivotal in interpreting the Parable of the Unforgiving Servant. The king’s decision to forgive the enormous debt of the servant is a powerful act of liberation. It’s not just about the king choosing not to hold the debt against the servant; it’s about completely freeing the servant from the bondage that the debt represented.

However, the unforgiving servant’s refusal to extend the same kind of release to his fellow servant illustrates a fundamental misunderstanding of the nature of forgiveness. His actions indicate a retention, a holding on to the debt, which is the opposite of aphiēmi.

Aphiēmi illuminates the disparity between the mercy shown by the king and the lack of mercy demonstrated by the unforgiving servant. It also underscores a key aspect of Christian teaching on forgiveness: it is not merely a moral duty but a call to emulate the liberating forgiveness that God offers us. As recipients of God’s immense grace, we are called to extend the same kind of freeing forgiveness to others.

Discussion question: Let’s reflect personally: Are there areas in our lives where we struggle to offer forgiveness? How can understanding God’s forgiveness towards us help us in extending forgiveness to others?

Consider the story of Joseph in Genesis 50:15-21 –

When Joseph’s brothers had seen that their father was dead, they said, “What if Joseph holds a grudge against us and pays us back in full for all the wrong which we did to him!” So they sent instructions to Joseph, saying, “Your father commanded us before he died, saying, ‘This is what you shall say to Joseph: “Please forgive, I beg you, the offense of your brothers and their sin, for they did you wrong.”’ And now, please forgive the offense of the servants of the God of your father.” And Joseph wept when they spoke to him. Then his brothers also came and fell down before him and said, “Behold, we are your servants.” But Joseph said to them, “Do not be afraid, for am I in God’s place? As for you, you meant evil against me, but God meant it for good in order to bring about this present result, to keep many people alive. So therefore, do not be afraid; I will provide for you and your little ones.” So he comforted them and spoke kindly to them.

Joseph forgives his brothers for their grave betrayal. This Old Testament story parallels the theme of undeserved forgiveness and reconciliation.

Discussion question: How can we cultivate a heart of forgiveness towards those who have wronged us?

This parable not only emphasizes the importance of forgiveness but also warns about the consequences of an unforgiving heart. It challenges us to reflect on our own willingness to forgive, understanding that forgiveness is a fundamental aspect of the Christian faith. Just as we have been forgiven much by God, we are called to extend forgiveness to others, reflecting God’s mercy in our relationships and communities.

Conclusion to Matthew 18

As we conclude our study of Matthew 18, we have traversed a rich landscape of teachings from Jesus, each part revealing important aspects of life within the kingdom of heaven. Let’s take a moment to reflect on the key lessons we’ve uncovered and consider how they apply to our lives today.

From Humility to Forgiveness: A Journey through Matthew 18

- The Heart of the Kingdom – Humility and Childlikeness: We began by exploring the concept of humility, understanding that to enter and be great in the kingdom of heaven, we must adopt a posture of humility, much like that of a child. This humility is not self-deprecation but a recognition of our proper place before God and others, characterized by trust, openness, and dependency.

- Stumbling Blocks and Temptations: We then delved into the serious responsibility we bear to not cause others to stumble in their faith journey. The vivid imagery used by Jesus in this teaching underscores the gravity of leading others into sin and challenges us to be mindful of our actions and their impact on our community.

- The Parable of the Lost Sheep: This parable illustrated the value God places on each individual, especially those who have strayed. It reminded us of the shepherd’s dedication and the importance of seeking out and caring for those who are lost or struggling in their faith.

- Restoring a Brother: We examined the process of addressing sin within the community, which balances truth and love, justice and grace. This step-by-step guide provided by Jesus emphasizes the goal of restoration and reconciliation, urging us to approach conflicts with a spirit of humility and a desire for healing relationships.

- The Parable of the Unforgiving Servant: Finally, we looked at the necessity of forgiveness. We learned that forgiveness in the biblical sense is not just about pardoning an offense but about liberating someone from the burden of that offense. This teaching calls us to extend grace and forgiveness to others, just as we have received it from God.

Final group discussion: After studying the various teachings in Matthew 18, which range from the nature of humility and dealing with sin in the community, to the importance of forgiveness and caring for the lost, how can we as individuals and as a community integrate these principles into our daily lives? In what specific ways can we embody the values of the kingdom of heaven in our interactions, both within our church and in our broader engagements with the world? (Or: how is humility and forgiveness connected?)

These teachings should shape our understanding of community life and our personal walk with Christ. The principles of humility, responsibility, care for the lost, reconciliation, and forgiveness are not just ideals; they are practical guidelines for living out our faith in everyday life.

Matthew 18 invites us to examine our hearts and actions, to embrace humility, to be mindful of how we influence others, to seek out those in need of guidance or support, to approach conflicts with a goal of restoration, and to practice forgiveness as a reflection of the grace we ourselves have received.

In our interactions with family, friends, and church members, let’s carry these lessons with us. Let’s mirror the kingdom values that Jesus teaches in Matthew 18 – marked by love, humility, care for one another, and a readiness to forgive.

As we conclude this study, may we be inspired to live out these teachings, bringing the light of Christ’s love and the principles of His kingdom into every aspect of our lives.

To God be the Glory, amen.

Leave a comment