I. Introduction: How Did the Magi Know?

Back in 2015, I traveled a lot more than I do today, and in December 2015, I found myself in the grand metropolis of Otley, UK. Now in the UK, I don’t know if they know what a warm sunny day is, but that weekend, the rain had stopped. It was still overcast, grey and chilly, but at least it wasn’t raining. I ventured out of my hotel room that weekend and stumbled upon a Victorian Festival. One of the first things I saw was a brass band. Now, I love a brass band, and this one even had a euphonium player. And as luck would have it, I came upon them just as they were ending their set, and I said, “Please just one more song? I came all the way from Texas!” And the leader says, “Ok, 1 more, just for you, do you have a request?”

And, realizing I would give this lesson on the magi 10 years later (or at least it makes a good story), I said, “How about, ‘We Three Kings?’” They mumbled to themselves and looked through their songbooks and said, “I think it’s #90.” And I said, “Yes, #90.” As if I knew what page number it was on.

So they gave me this special gift of song that I’d like to share with you:

We might be beginning with a musical selection of “We Three Kings,” but we’re going to go a lot deeper. I hope today isn’t just a musical or geographical journey; I hope to intertwine prophecy, a cosmic battle, and the unfolding of God’s redemptive plan, starting with: What did the Magi know, and how did they know it?

In today’s lesson, we are going to delve into how the Magi’s understanding, deeply rooted in the prophetic scriptures of Daniel and Isaiah, led them to follow the extraordinary star to Jesus. Their journey, far more than just a crossing of deserts, symbolizes the revelation of the Messiah to all nations, transcending cultural and geographical boundaries. We will explore how this journey, shrouded in mystery, places the Magi as key witnesses in the Nativity story, set against a backdrop of a heavenly struggle between God’s redemptive plan and Satan’s attempts to thwart it. This cosmic battle intersects with King Herod’s turbulent reign, adding depth to the struggle. The Magi’s journey, illuminated by the “star out of Jacob” mentioned in the book of Numbers and the prophecies of Isaiah about nations drawn to the light, beautifully aligns with Old Testament prophecies, showcasing the fulfillment of God’s divine plan. These pivotal moments bridge the Old and New Testaments, highlighting God’s consistent presence in the ongoing story of salvation.

In summary, the Magi’s journey is not just a path to a manger; it’s a saga that connects prophecy, history, and God’s overarching plan for humanity.

Ready? Here we go.

II. Who Are the Magi?

If you have your bibles handy, which you probably should because, after all, this is a bible study, we’re going to spend time in Matthew 2 which is the only gospel that tells us about the magi.

Matthew 2:1-2,

Now after Jesus was born in Bethlehem of Judea in the days of Herod the king, magi from the east arrived in Jerusalem, saying, “Where is He who has been born King of the Jews? For we saw His star in the east and have come to worship Him.”

Discussion: The Magi saw the star and acted.

What has God used to get your attention and point you toward Christ—and did you respond immediately, slowly, or not at all?

The Magi from the east were enigmatic visitors, guided by a star, and they embody the fulfillment of prophecies like Numbers 24:17 which we’ll get into more detail later. The origins of the magi, their numbers, and their names are shrouded in mystery, leaving much to our research, imagination and faith. They brought three gifts – gold, frankincense, and myrrh – and so tradition and songs have led many to assume there were three Magi. In reality, there were likely many more. And although sometimes they are referred to as “kings,” Scripture itself never calls them kings. I personally believe the three magi were firefighters. I believe this because scripture says they came from afar.

Ok, just kidding. Early Christians probably considered them kings because of Old Testament prophesies such as Psalm 72:9-11,

Let the nomads of the desert bow before him,

And his enemies lick the dust.

Let the kings of Tarshish and of the islands bring presents;

The kings of Sheba and Seba offer gifts.

And let all kings bow down before him,

All nations serve him.

The Magi in the Nativity story have a rich and varied history.

In the Greco-Roman world, the term magi often referred to people viewed as intermediaries between the divine and humanity—wise men, scholars, or priestly figures who interpreted dreams and studied the heavens. Matthew’s original audience would likely have heard “Magi” and thought of learned men with a deep connection to the spiritual realm.

In the Greek text of Matthew 2:1–12, the word Magi (Greek: μάγοι, magoi) suggests eastern, probably Persian or Babylonian, origins and a role as learned astrologers or priests.

Fun fact: “magi” is plural. The singular term is “magus.”

In the book of Daniel, we also meet a group of royal advisers: wise men, magicians, enchanters, and astrologers who served in the courts of Babylon and Persia. Daniel is placed over these men. Later Greek translations often use the word magoi for this class of advisers. In Daniel 2:48, Daniel is appointed as “ruler over the whole province of Babylon and chief prefect over all the wise men of Babylon.”

So while the Bible doesn’t say “Daniel was a magus,” there is a strong link between Daniel and the tradition of eastern wise men. It is very possible that the Magi of Matthew 2 stand in that same tradition—learned men from the regions once ruled by Babylon and Persia, where Daniel served.

Historically, many of these eastern “wise men” have been associated with priestly groups from Media and Persia, and later writers connect them with Zoroastrianism. That means the Magi in Matthew 2 were likely priests or scholars from that part of the world, familiar with watching the stars and, through Daniel’s influence generations earlier, likely exposed to the Hebrew Scriptures and the promise of a coming King.

Their understanding of Daniel’s prophecies and other Old Testament passages may explain why, when they saw an unusual star, they concluded that the “King of the Jews” had been born and began their long journey during King Herod’s troubled reign.

Early Christian writings and art further highlight the Magi’s significance. The early Church Fathers saw their journey as a sign that the Messiah was revealed not only to Israel but also to the Gentiles. In early Christian art, the Magi are often depicted in eastern or Persian-style clothing, underscoring their foreign origin and the global reach of Christ’s birth. They came as representatives of the wider world, proclaiming that Christ is for all nations, not just for the Jews.

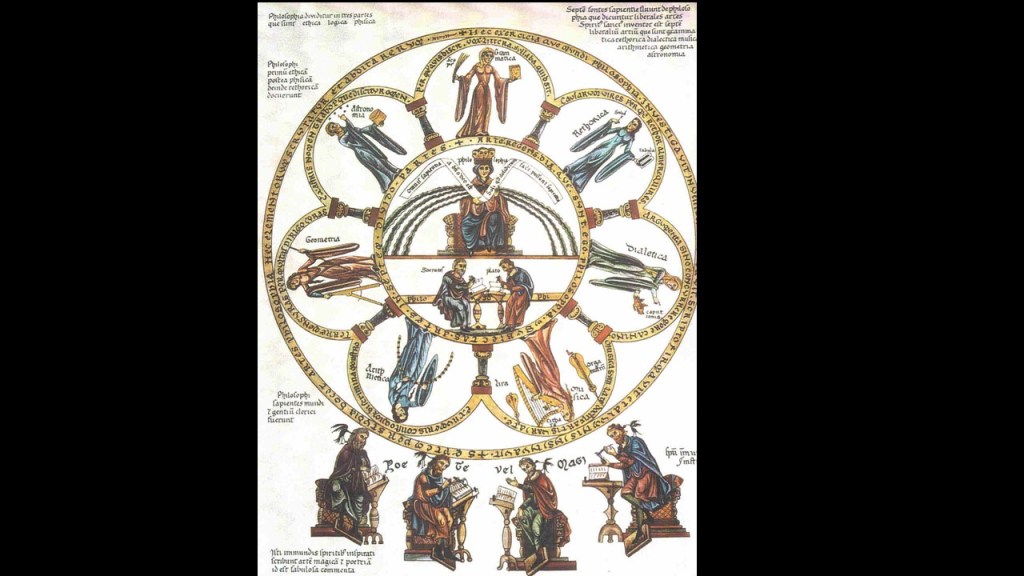

By around 500 AD, commentators had begun to call the Magi “kings,” and by the twelfth century, tradition had even given them names—Balthazar, Caspar, and Melchior, as depicted in Herrad of Landsberg’s Hortus Deliciarum. Different Christian traditions have added their own color: for example, Chinese Christians sometimes suggest that one of the Magi may have come from the Far East.

However, the idea that the Magi were literally kings was challenged by Reformers like John Calvin, who pointed back to the simple language of Scripture. Even so, the image of “three kings” has remained deeply embedded in popular Christian tradition.

One more detail: contrary to the typical nativity scene, these wise men almost certainly didn’t arrive on the night of Jesus’ birth. Considering their likely origin in the east and the distance involved, many scholars suggest their arrival in or near Bethlehem could have been as much as two years after Jesus’ birth. This also fits with Herod’s decision to kill the boys in Bethlehem “two years old and under.” The Magi’s journey, then, was not a quick detour, but a long and costly expression of faith, seeking the newborn King.

III. The Significance of the Magi’s Gifts

The magi brought 3 gifts which is why tradition considers them the 3 magi. What were the gifts of the Magi?

Not that 1905 O. Henry story I once wrote a high school essay on, you know the story of the young wife who sells her hair to buy a platinum chain for her husband’s gold family heirloom watch, only to find he had sold the watch to buy a set of expensive ornamental hair combs.

No, the gifts of the magi are listed in Matthew 2:11 –

And when they were come into the house, they saw the young child with Mary his mother, and fell down, and worshipped him: and when they had opened their treasures, they presented unto him gifts; gold, and frankincense and myrrh.

These are not just material offerings, but gifts rich in meaning. Christians throughout church history have seen in them a picture of Jesus Christ’s identity and mission.

The Magi presented their gifts to the young child—a real treasure. When we see Christmas scenes of the Three Wise Men, they’re often shown holding a small decorative container with a gift. It’s likely, though, that the Magi brought substantially more. They certainly wouldn’t travel hundreds of miles just to deliver samples. No, they brought gifts fit for the King of Kings.

Many Bible teachers have suggested that when Mary and Joseph later fled to Egypt, the resources from these gifts may have helped sustain them during their time there. Scripture doesn’t say that explicitly, but it would be just like God to provide exactly what they needed, exactly when they needed it.

- Gold: The Symbol of Divine Kingship

Gold certainly makes sense as a gift. Gold is a gift fit for a king, and the Magi recognized that this child was the rightful King of Israel. Matthew has already shown us that Jesus’ lineage traces back to David and Abraham, just as Scripture prophesied.

The Magi don’t just call Him a king; they give Him gold as to a king. It’s as if Matthew wants to make sure we understand, as the Magi did, that Jesus wasn’t just born into royalty—He was born a King.

Throughout Scripture, gold is associated with wealth, majesty, and even the presence of God Himself, often used in the Tabernacle and later the Temple to signify God’s holiness. By offering gold, the Magi are, in effect, recognizing the child before them as a royal figure, fulfilling the spirit of prophecies like Psalm 72:14–15:

He will rescue their life from oppression and violence,

And their blood will be precious in his sight;

So may he live, and may the gold of Sheba be given to him;

And let them pray for him continually;

Let them bless him all day long.

This also echoes Isaiah 60:6, which speaks of nations bringing gold in honor of the Lord. Gold, then, points us to Jesus as the divine King—the One who rules with justice and righteousness, the King of Kings and Lord of Lords.

- Frankincense: A Symbol of Priesthood and Sacrifice

The second gift, frankincense, would have been instantly familiar in the religious life of Israel. Frankincense is a fragrant resin used in worship, especially in the Temple, where it was burned as part of the incense offering. Its aroma rising heavenward was a picture of prayer and worship ascending to God.

By bringing frankincense, the Magi honor Jesus not only as King but as someone uniquely connected to God—a priestly figure. Christians have long seen in this gift a picture of Christ as our great High Priest.

This fits beautifully with the promise of Psalm 110:4:

The Lord has sworn and will not change His mind,

“You are a priest forever

According to the order of Melchizedek.”

And with the New Testament explanation in Hebrews 2:17

Therefore, He had to be made like His brethren in all things, so that He might become a merciful and faithful high priest in things pertaining to God, to make propitiation for the sins of the people.

Jesus bridges the gap between a holy God and sinful people. While Herod schemes to preserve his fragile earthly power, the Magi bow before a child who will one day offer Himself as the perfect sacrifice and intercede for His people forever.

Frankincense, then, points us to Jesus as the priestly mediator—the One whose life, death, and resurrection make it possible for us to come into the presence of God.

Which brings us to the third gift.

- Myrrh: The Emblem of Suffering and Redemption

Myrrh is a strange gift for a baby. Myrrh is an aromatic resin used in perfumes, anointing oils, and—most significantly—in burial customs. Why give myrrh, a symbol so closely associated with death, to a newborn child?

Because Jesus was born for a purpose that reached beyond the manger. From the beginning, His mission involved suffering and sacrifice.

Jesus Himself says in Matthew 20:28:

“The Son of Man did not come to be served, but to serve, and to give His life a ransom for many.”

In John 12:27, as He looks ahead to the cross, He says:

“Now My soul has become troubled; and what shall I say, ‘Father, save Me from this hour’? But for this purpose I came to this hour.”

Myrrh appears again in the Passion narrative. In Mark 15:23, Jesus is offered wine mixed with myrrh as a pain-dulling drink during His crucifixion. Then in John 19:39–40, Nicodemus brings a mixture of myrrh and aloes—about seventy-five pounds’ worth—to prepare Jesus’ body for burial.

So from cradle to cross, myrrh reminds us that this child’s story would lead to a tomb—and then to an empty tomb. The gift of myrrh points to Jesus as the suffering Savior, the One who would die for our sins, be buried, and rise again in victory.

When we put these three gifts together, we see a rich portrait of Christ:

- Gold — for His royal authority: Jesus is King.

- Frankincense — for His priestly role: Jesus is our High Priest.

- Myrrh — for His suffering and death: Jesus is our Sacrifice.

The Magi may not have understood every detail of how God would work all this out, but their gifts—guided by God’s providence—testify to who Jesus is. He is the King who rules, the Priest who intercedes, and the Savior who gives His life to redeem us.

These gifts are more than part of a Christmas decoration. They point us to the heart of the gospel and invite us, like the Magi, to worship Jesus with our very best.

IV. The Prophetic Tapestry Behind the Magi’s Journey

Where did the Magi come from, and how did they know what they were looking for?

As we look into their journey, we uncover a rich tapestry of prophecy and scriptural insight. Their pursuit, very likely shaped by an awareness of Isaiah’s and Daniel’s prophecies, reveals a profound convergence of celestial signs and divine revelation.

Let’s start with Isaiah.

- Light to the Nations: Isaiah’s Prophecies

In Isaiah’s prophecies, we find key passages that point forward to a coming King and a dawning light.

Isaiah 9:6-7: A Child is Born

For a child will be born to us, a son will be given to us;

And the government will rest on His shoulders;

And His name will be called Wonderful Counselor, Mighty God,

Eternal Father, Prince of Peace.

There will be no end to the increase of His government or of peace,

On the throne of David and over his kingdom,

To establish it and to uphold it with justice and righteousness

From then on and forevermore.

The zeal of the Lord of hosts will accomplish this.

This prophecy speaks of a child who is not only a king, but bears titles that belong to God Himself. The promise of an eternal, righteous government fits perfectly with the Magi’s question: “Where is He who has been born King of the Jews?” They are not just looking for a local prince; they are looking for the promised ruler.

Isaiah 60:1-6: Nations Coming to the Light

“Arise, shine; for your light has come,

And the glory of the Lord has risen upon you.

…Nations will come to your light,

And kings to the brightness of your rising.

…They will bring gold and frankincense,

And will bear good news of the praises of the Lord.”

Here we see nations and rulers drawn to God’s light and bringing gifts—gold and frankincense—to honor the Lord. It’s hard not to think of the Magi when we read this. Matthew doesn’t quote Isaiah 60 directly, but the pattern is similar: Gentiles, drawn by light, bringing gifts to the One God has exalted.

The Magi’s journey is a living picture of these themes: the nations coming to the light of God’s glory in Christ.

- Daniel’s Timetable: A Clue to the “When”

If Isaiah gives us a sense of who is coming, Daniel helps us think about when.

The book of Daniel, especially chapters 7–9, is filled with visions and prophecies about future kingdoms and the coming of “the Anointed One.” One key passage is the prophecy of the Seventy Weeks in Daniel 9:24–27.

Daniel 9 speaks of “seventy weeks” decreed for God’s people and the holy city. In prophetic language, many conservative scholars understand these “weeks” as weeks of years—sets of seven years each. That would make the seventy weeks a period of 490 years. During this time, God would deal with sin, bring in righteousness, and ultimately present “Messiah the Prince.”

The prophetic clock begins “from the issuing of a decree to restore and rebuild Jerusalem” (Daniel 9:25). One very influential view, popularized by Sir Robert Anderson in The Coming Prince, sees this decree in the events of Nehemiah 2, when Artaxerxes authorized the rebuilding of Jerusalem’s walls. Counting forward from that point, using prophetic years, Anderson and others have argued that the sixty-nine weeks (483 years) bring us to the time of Jesus’ public presentation in Jerusalem—what we call the Triumphal Entry.

After this period, Daniel says that “the Messiah will be cut off” (Daniel 9:26), a phrase that fits well with the crucifixion.

Now, did the Magi sit down with copies of Daniel and a calculator? Scripture doesn’t say. But it is at least possible that wise men in the East, if they had access to Daniel’s writings (and remember, Daniel was a high official in Babylon and over the wise men), could see that they were living in the general time period when Messiah was expected.

They would also know, from the Law, that priests began their service around age thirty (Numbers 4), and that Jesus later begins His public ministry “about thirty years of age” (Luke 3:23). If they connected Daniel’s timetable with the idea that the Anointed One would minister and then be “cut off,” it’s not hard to imagine scholars like the Magi realizing that the window for Messiah’s birth had opened.

We cannot be dogmatic about this. The Bible does not spell out their calculations. But Daniel’s prophecy gives a strong sense that the timing of Messiah’s coming was not random—it was part of God’s precise plan.

- Other Prophetic Markers: Tribe, Town, and Star

Genesis 49:10 – The Scepter of Judah

The scepter shall not depart from Judah,

Nor the ruler’s staff from between his feet,

Until Shiloh comes,

And to him shall be the obedience of the peoples.

This prophecy ties kingship to the tribe of Judah and looks forward to a final ruler—“Shiloh”—to whom the obedience of the peoples will belong. Jesus, born of the line of Judah and David, fulfills this expectation. His first coming anticipates the ultimate fulfillment when every knee bows and every tongue confesses Him as Lord.

Micah 5:2 – The Birthplace in Bethlehem

But as for you, Bethlehem Ephrathah,

Too little to be among the clans of Judah,

From you One will go forth for Me to be ruler in Israel.

His goings forth are from long ago,

From the days of eternity.

Micah pinpoints Bethlehem as the birthplace of the coming ruler whose origins are “from the days of eternity.” When Herod asks the chief priests and scribes where the Messiah is to be born, they quote this verse (Matthew 2:4–6). Whether the Magi knew Micah ahead of time or learned it in Jerusalem, their journey is now narrowed to a specific town.

The Star: A Heavenly Sign

Matthew 2:1–2 says:

Now after Jesus was born in Bethlehem of Judea in the days of Herod the king, magi from the east arrived in Jerusalem, saying, “Where is He who has been born King of the Jews? For we saw His star in the east and have come to worship Him.”

More literally, the phrase can mean “we saw His star in its rising.” The point is that the Magi, who watched the skies for signs, saw something so unusual that they connected it with the birth of the promised King.

What was this star (astēr)?

- Some have suggested a conjunction of planets,

- others, a comet or a supernova,

- and some view it as a unique, miraculous light sent by God.

The way Matthew describes the star—appearing, disappearing, and then “standing over” where the child was—suggests more than a normal astronomical event. At the very least, this was a sign from God that the Magi could recognize.

This fits well with Numbers 24:17:

“I see him, but not now;

I behold him, but not near;

A star shall come forth from Jacob,

A scepter shall rise from Israel…”

Many Jewish and Christian interpreters have seen this “star” as a prophetic picture of the coming Messiah. So when the Magi say, “We have seen His star,” they are responding to a sign that lines up with what Scripture had foretold.

- Pulling the Threads Together

When we weave these threads together—Isaiah’s promises, Daniel’s timetable, the tribal promise of Genesis, the birthplace in Micah, and the star in Numbers—we begin to see why the Magi’s journey is so significant.

Their trip was not just a romantic story about exotic travelers and camels. It was an example of how God’s revelation in Scripture and God’s revelation in creation (the star) come together to point to Jesus. Human wisdom alone would never have found Him, but God used the very things these men knew—texts, timelines, and the night sky—to bring them to His Son.

The journey of the Magi highlights the connection between divine revelation and human pursuit. Their interpretation of the star as a sign of the Messiah’s birth demonstrates how God can use both His written Word and His world to draw people to Christ. The Magi’s story affirms that the Messiah is not only the hope of Israel, but the Savior for the nations.

V. Satan’s Attempts to Prevent the Birth of Christ

But all is not well in the world that Satan rules. From the earliest pages of Scripture, there is a real spiritual conflict running behind human history. God promised a coming Deliverer in Genesis 3:15, and ever since, there has been opposition—sometimes subtle, sometimes violent—aimed at stopping God’s redemptive plan.

Now, just to be clear, Satan is not equal to God. God is sovereign, and Satan is a creature on a leash. But the Bible does show us that Satan opposes God’s plan and often works through human sin, human fear, and human rulers who cling to power.

One of the clearest early examples is Cain and Abel. In Genesis 4, Cain’s jealousy turns into murder. And the New Testament gives us a glimpse behind the curtain: 1 John 3:12 says Cain “was of the evil one and murdered his brother.” That doesn’t mean Cain wasn’t responsible—he absolutely was—but it shows that the conflict is bigger than Cain’s emotions. From the first family, there is already hostility toward what God is doing.

Fast-forward through the Old Testament and you see the pattern repeat: God preserves His people and His promise, while attacks rise up against the line of blessing. Sometimes it’s oppression. Sometimes it’s attempted extermination. Sometimes it’s internal corruption. Yet every time, God keeps His word. The promised Savior is not hanging by a thread; He is moving forward on God’s timetable.

And then Revelation 12 gives us a vivid picture of what’s happening at the spiritual level. John describes a great dragon waiting to devour the male child as soon as He is born. That’s symbolic, of course, but the message is clear: Satan is not indifferent to the arrival of Christ. He hates the Messiah, and he wants Him destroyed before He can complete His mission.

Which brings us to Herod. By the time we are in Matthew 2, the promise has narrowed—tribe of Judah, line of David, birth in Bethlehem. The Magi arrive asking about a newborn King, and Herod is disturbed. He’s threatened. He’s calculating. He plays the part of a worshiper, but he’s really hunting a rival.

From a human standpoint, Herod is acting out of paranoia and political self-preservation. But spiritually, he fits the pattern we’ve been tracing: when the promised King arrives, opposition rises to meet Him. Herod becomes the latest tool in that long attempt to crush God’s promise at the moment it enters the world.

And here’s the point: Satan’s opposition is real—but it never wins. God guides the Magi, warns them in a dream, warns Joseph in a dream, and protects the child. Herod rages, but God reigns. The Messiah will not be stopped. Jesus was not born by accident, and He will not be removed by force. He came exactly when He was meant to come, and He will accomplish exactly what the Father sent Him to do.

As we watch Herod’s response unfold, keep this in mind: Matthew is showing us more than political drama. He is showing us a clash between a temporary throne that is terrified of losing power—and the true King whose kingdom cannot be shaken.

VI. Herod’s Attempt to Kill the Newborn King

But Satan isn’t finished. What he tried to do in centuries past, now he’ll attempt to do through King Herod. We began in Matthew 2:1 –

After Jesus was born in Bethlehem in Judea, during the time of King Herod, Magi from the east came to Jerusalem

Did you know there are actually two towns named Bethlehem? One was in the territory of Zebulun (mentioned in Joshua 19:15), and the other was Bethlehem in Judea, about six miles south of Jerusalem. It is this Bethlehem of Judea that Micah 5:2 points to and where Jesus was born.

When I visited Israel 12 years ago, I didn’t go into Bethlehem, but I did get a chance to photograph it from a distance. Today it’s largely under Palestinian control, and over the centuries the original village has been destroyed and rebuilt multiple times. The Church of the Nativity complex doesn’t look anything like the humble setting of our Lord’s birth. What I find especially interesting is that this area around Bethlehem was associated with sheep and shepherds. Many Bible teachers have suggested that sheep raised there supplied lambs for sacrifice at the Temple in Jerusalem, including Passover lambs. It’s fitting that the One John the Baptist will later call “the Lamb of God” is born in a place known for flocks.

Herod was born around 74 B.C. Through political maneuvering and Roman support, he was declared “king of the Jews” by the Roman Senate around 40 B.C. and secured his rule over Jerusalem a few years later. He ruled for decades with Rome’s backing. To strengthen his claim to the Jewish throne, he married a Hasmonean princess, Mariamne, but he already had a wife named Doris and a son, Antipater, whom he later banished. Herod’s personal life was a mixture of political calculation and paranoia. He executed rivals, including members of his own family—eventually including Mariamne herself. It’s not hard to see why the Jews questioned his legitimacy.

By the time Jesus was born, Herod had been on the throne for many years. He had rebuilt and expanded the Temple in Jerusalem and left impressive buildings throughout the land. But underneath his building projects was a deeply insecure man who would do anything to protect his power.

Interestingly, there was a wider atmosphere of expectation in the ancient world around this time. Later Roman historians look back and describe an old belief that a ruler would arise from Judea:

- Suetonius writes of “an ancient and settled expectation throughout the East, that a man from Judea would obtain the rule of the world.”

- Tacitus records a similar conviction that about that time “those from Judea” would gain power over the world.

- The Jewish historian Josephus mentions that many Jews believed a world ruler would arise from their nation.

There was a sense, even among pagans, that something significant was going to come out of Judea. The birth of Christ, then, was not just a local event; it fulfilled the hopes of Israel and exposed the fears of earthly rulers like Herod.

We pick up the story in Matthew 2:3:

When King Herod heard this he was disturbed, and all Jerusalem with him.

Herod knew he had no true Davidic claim to the throne. The phrase “all Jerusalem with him” likely refers to the way his paranoia and violent reactions threw the whole city into turmoil. If Herod felt threatened, everyone knew trouble was coming.

This connects with the earlier prophecy of Genesis 49:10:

The scepter will not depart from Judah, nor the ruler’s staff from between his feet, until he comes to whom it belongs and the obedience of the nations is his.

Herod was not of the tribe of Judah, so the scepter of the king did not belong to him. He was a pretender trying to hold what God had promised to another.

Matthew 2:4-6

When he had called together all the people’s chief priests and teachers of the law, he asked them where the Messiah was to be born. “In Bethlehem in Judea,” they replied, “for this is what the prophet has written:

“‘But you, Bethlehem, in the land of Judah,

are by no means least among the rulers of Judah;

for out of you will come a ruler

who will shepherd my people Israel.’”

This prophecy is from Micah 5:2, and they’re explaining to Herod that this prophecy has already come true, and that magi are here to pay homage to Him. Herod likely gathered the priests and rabbis of the Sanhedrin, and in the NIV Herod sounds very nice, he asked them politely where Christ the Messiah would be born. I think it’s more of a demand; Herod is the political ruler with a history of executing people he doesn’t like, and Herod wants to know if there’s any validity to this threat.

Matthew 2:7-8

Then Herod called the Magi secretly and found out from them the exact time the star had appeared. He sent them to Bethlehem and said, “Go and search carefully for the child. As soon as you find him, report to me, so that I too may go and worship him.”

I don’t think Herod’s being honest here, just sayin’. Herod meets with the magi privately and interrogates them for intel. No doubt he did this away from the Sanhedrin, for the Sanhedrin would understand exactly why Herod wants to know the time and place of the birth of Christ. He would understand that Jesus may be as old as two years old now, given the length of the journey from Persia.

Did I mention earlier that Bethlehem is only about 6 miles away? Don’t you think it’s odd that Herod knows the fulfillment of prophecy is just a short distance, yet he sends nobody with the magi. Herod certainly didn’t want the Jews to know what the magi already did, that the king of the Jews was born. The Jews in Herod’s palace were likely to set up the newborn king as the new king of the Jews with the intention of overthrowing Herod.

Matthew 2:9-10

When they had heard the king, they departed; and, lo, the star, which they saw in the east, went before them, till it came and stood over where the young child was. When they saw the star, they rejoiced with exceeding great joy.

To me, it’s interesting that the Jews, though they knew prophecy, did not accompany the magi. Did the Jews even know the Messiah had been born? This passage seems to indicate that the star had reappeared – that “lo” in verse 9 is an expression of surprise and joy. The Magi, Gentiles from far away, are overjoyed to see God’s guidance confirmed. Meanwhile, the people living in Jerusalem—who have the Scriptures and are only a short walk away—do not move. It’s a sobering contrast: outsiders travel far to find the King, while those closest to the truth stay home. Here are the contrasts between the magi and Herod that Matthew identifies:

|

Herod |

Magi |

|

Sought to destroy |

Sought to worship |

|

Disturbed |

Rejoiced |

|

Calculated / Delayed |

Responded / Went |

|

Manipulative (“tell me so I can…”) |

Obedient (warned by God; went another way) |

|

Saw a threat to his throne |

Saw the rightful king / promised Messiah |

|

Used violence |

Offered gifts |

|

Clung to a temporary kingdom |

Honored a King worth any cost |

Discussion: Herod saw a threat; the Magi saw a King worth worshiping.

When Jesus presses on your life—your schedule, comfort, control—do you tend to respond more like Herod or more like the Magi?

We know the rest of the story. The Magi find the child, bow down, and offer gifts. Then we read in Matthew 2:12:

And having been warned by God in a dream not to return to Herod, they left for their own country by another way.

Herod, furious that the Magi do not come back, orders the killing of all the boys in Bethlehem two years old and under (Matthew 2:16). This horrific act is remembered as the Massacre of the Innocents and is tied by Matthew to Jeremiah’s prophecy of Rachel weeping for her children (Jeremiah 31:15). It is another flashpoint in the spiritual conflict we talked about earlier—Satan working through human rulers to try to destroy God’s promised King.

But once again, God is ahead of the enemy. Joseph is warned in a dream to flee to Egypt, and the family escapes. Herod dies; Jesus lives.

I love that final line about the Magi: “they left for their own country by another way.” It’s more than just a change of route. Once you have truly met Jesus, you do not go back the same way. He changes our direction.

The Christmas tradition of exchanging gifts is probably influenced by the story of the Magi, but the real story of Christmas is not our gifts to one another—or even the gifts of the Magi to Jesus. The real story is the gift of God’s Son. When God gave us Jesus, He gave us all that heaven could give. Ephesians 1:3 says that God has blessed us “with every spiritual blessing in the heavenly places in Christ.” In Christ, God has already wrapped up every blessing and handed it to us.

VII. Conclusion: The Lasting Impact of the Magi’s Journey

We began with a simple question from Matthew 2:1–2:

“Where is He who has been born King of the Jews? For we saw His star when it rose and have come to worship Him.”

The Magi, those wise men from the East, did not stumble into this question by accident. Their journey was shaped by God’s revelation—by prophecies like Isaiah and Micah, by the promise of a coming King from Judah, and by a star that God used to draw them to Jesus.

They knew who they were seeking: the promised Messiah, born King of the Jews.

They knew why they were seeking Him: “we have come to worship Him.”

They had some sense of when to look, living in the time when God’s prophetic clock was nearing the arrival of the Anointed One.

And by the time they reached Jerusalem, they were told where to find Him—Bethlehem, just as the prophet had written.

Their journey was long, costly, and intentional. They traveled far, brought significant gifts, and when they finally saw the child, they fell down and worshiped. Their gifts—gold, frankincense, and myrrh—paint a picture of who Jesus is:

- Gold for the King who rules.

- Frankincense for the High Priest who brings us to God.

- Myrrh for the Savior who would suffer, die, and rise again.

In contrast, many in Jerusalem—including the religious leaders who could quote Micah 5:2 from memory—never walked the six miles to Bethlehem. They had the Scriptures but did not seek the Savior. Herod heard the same news and responded not with worship, but with fear and rage.

That contrast still speaks to us. The Savior has already come. The greatest gift has already been given. We know far more than the Magi knew:

- We look back on the cross, not just the cradle.

- We know about the empty tomb, not just the star.

- We have the complete Scriptures, not just scattered prophecies.

The real question for us is no longer, “Where is He?” The question is, What will we do with Him?

James 4:8 says,

“Draw near to God and He will draw near to you.”

Jesus wants to be found. We don’t need a star in the sky; we have the Word of God in our hands, the testimony of believers through the ages, and the Holy Spirit working in hearts today.

The Magi remind us that those who truly seek Jesus will find Him—and when they do, they cannot go back the same way. Matthew tells us the Magi “returned to their own country by another way.” That was true of their route, but it’s also true of their lives. We all meet Jesus – and after we meet Him, we go another way. No one meets the true King and remains unchanged.

Discussion: They didn’t go back the same way.

What is one specific “another way” you need to walk this week because you’ve met Jesus?

As we celebrate Christmas, may we respond like the Magi:

- Seeking Jesus earnestly, not casually.

- Believing what God has said about His Son.

- Worshiping Him with our best—our time, our obedience, our hearts.

The story of the Magi is more than a beautiful detail in a nativity scene. It is an invitation. The King has come. Gentiles from far away bowed before Him. Herod feared Him. Religious leaders ignored Him.

Each of us must decide where we stand.

For the indescribable gift of His Son, may our hearts be filled with the wonder and joy of that first Christmas, and may the love of Christ lead us, like the Magi, to bow in worship before the true King.

To God be the glory. Amen.

Leave a comment